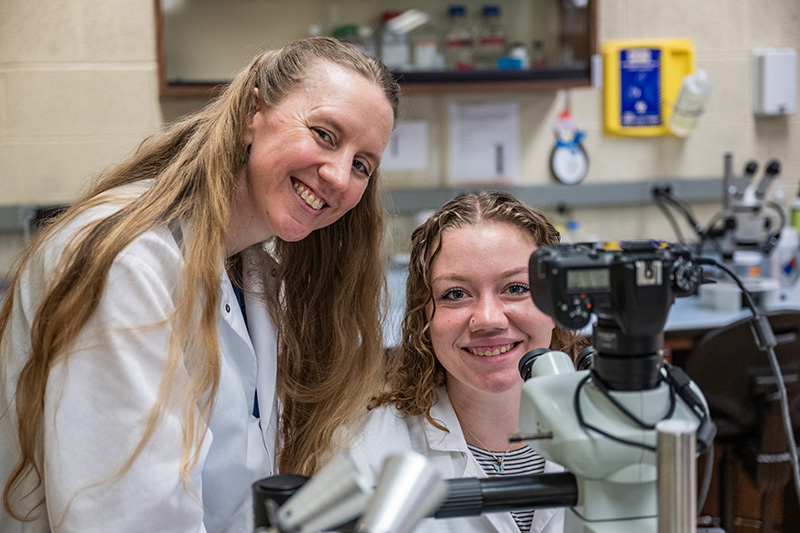

Sara McClelland and Emma Pollackov’25 conduct microdissections on tadpoles for research into the effects of microplastics on animal physiology.

We eat, drink, and breathe them—plastics.

Microplastics (pieces of plastic no bigger than a grain of rice) and nanoplastics (not visible to the naked eye) are in our food, water, and air. Several studies have confirmed that these plastics have infiltrated our lungs, kidneys, livers, and brains, among other organs, and recent research that compared human autopsy samples from 2016 with those from 2024 saw a 50 percent increase in plastics concentration.

While experts speculate about the health effects of these ingested and absorbed micro- and nanoplastics, very little research has been done on the potential health hazards. Sara McClelland, associate professor of biological sciences, has received a $500,846 grant to do just that.

The grant was awarded by the National Science Foundation’s program Building Research Capacity of New Faculty in Biology (BRC-BIO). It funds McClelland’s project—“BRC-BIO: Undergraduate Researchers Investigating the Biological Effects of Environmental Microplastics”—over the next three years.

McClelland describes herself as an ecological physiologist. “I like to understand how the environment is impacting the way the body works,” she says. “There are a lot of open-ended questions regarding the impact of microplastics, and I started work on these questions here at Moravian two years ago.”

McClelland tells the story of when she asked her research student at the time to look through the primary literature for work that had been published on the effects of microplastics on the body. At their meeting the following week, he told her that he couldn’t find anything and wondered if he was using the correct search terms. “We looked through Google Scholar and searched all the databases Reeves Library has to offer—nothing,” says McClelland. “I reached out to some colleagues and people in the field who do some work with microplastics. They said, ‘No one’s done that research.’”

And so began McClelland’s pioneering research and the path to her grant.

She and her research students are working with tadpoles as they develop into juvenile frogs, which she explains are often used in the study of human development because they undergo similar developmental processes. McClelland’s team is exposing tadpoles to different levels of microplastics that humans are commonly exposed to in food, water, and the air.

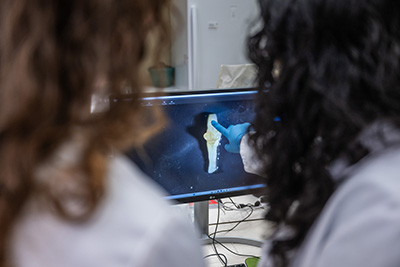

“Right now, I am looking at how microplastics impact the digestive system, in particular the anatomy of the digestive tract, as well as the microbiome, which can have significant effects on the brain,” McClelland says. “We’ll also use fluorescent microplastics to see where the microplastics end up in the body.”

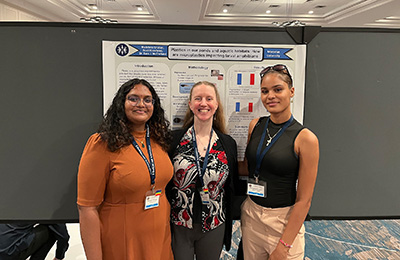

The grant also funds a considerable amount of student research, SOAR projects, and travel to conferences. Taking students to conferences to present their work is one of the highlights of McClelland’s role at Moravian. “They get very nervous because they will be in front of professional scientists, but they come away from these events so energized and much more confident about being scientists. After they give their presentation, they are asked questions by scientists they don’t know, and they are able to hold conversations about their research. They come up to me and say, ‘Dr. McClelland, I knew the answers to their questions. We had actual conversations about the research!’”

McClelland’s funding is the latest of four research grants awarded to Moravian University’s biology professors over the past year and a half. Their work will advance scientific understanding of important issues while providing uncommon research opportunities for undergraduate students. “Our department has worked very hard to build a culture of student research,” says McClelland. “We have an increasing number of students who want to do research, and getting grants like this enables us to give students these opportunities that set them up for future success in graduate school or a career. They are doing hands-on independent research that puts them in a class above their peers from other institutions.”