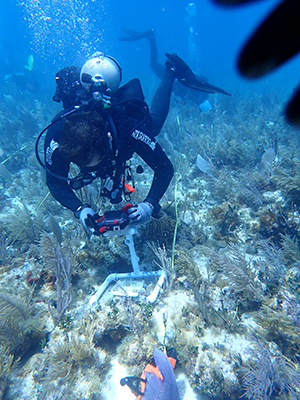

Brian Reckenbeil ’09 heading out for "field" research into preserving Florida's Coral Reef.

by Therese Ciesinski

Florida’s Coral Reef is the only coral reef system in the continental United States. The third largest in the world, it stretches 360 miles along the southeastern part of the state, from the St. Lucie Inlet south past the Keys to Dry Tortugas National Park.

The reef provides food and shelter for countless varieties of sea life. Coral is a keystone species, an organism whose presence is essential in order for other living creatures to survive. Along with many reefs worldwide, Florida’s is at risk from rising water temperatures, pollution, and disease. As the reef declines, so does the life that depends on it.

The Coral Conservation Program (CCP) at The Florida Aquarium in Apollo Beach is researching the best methods to breed and protect coral, now and in the future. A Moravian grad is part of the team.

Brian Reckenbeil ’09 joined the aquarium as a coral restoration manager in 2021. A biology major as an undergrad, he was studying abroad in Bonaire and the Galapagos, and that experience ignited his passion for marine biology. He earned his master’s in natural resources from Delaware State University in 2013.

Reckenbeil is part of a team conducting cutting-edge research focused on breeding Caribbean coral in the lab with the goal of increasing the animals’ genetic diversity and resistance to the effects of climate change.

“Land-based breeding is super important for the future because we want to increase genetic diversity, and you can control things better in the lab,” Reckenbeil says. “Indoors, we artificially control the solar/lunar cycles and water temperature to make corals “think” they’re in the ocean. We have a fertilization rate over 90 percent.”

The researchers hope that breeding individual corals of the same species will improve their overall resistance to disease, temperature changes, water salinity, and the effects of rising sea levels. The goal isn’t the immediate repopulation of the reef, but to raise new corals for observation and research.

When a coral spawns, the union of egg and sperm form a larva. This larva is carried by currents until it settles onto suitable habitat, where it will remain its entire life, unless whisked away by strong ocean currents such as those produced by a hurricane.

Breeding coral is challenging. Individual corals spawn once a year, typically after sunset. If researchers don’t collect the eggs and sperm at that time, it can be 365 days before there’s another chance. Once collected, there’s only an hour or two to fertilize the eggs.

“The CCP has spawned 14 Caribbean coral species so far,” Reckenbeil says. “We’ve created over 10,000 individual baby corals, each genetically different, that have been returned to the ocean.” The lab-bred corals are now producing offspring of their own. Researchers’ future goals include getting lab coral to spawn in the wild.

Increasing science’s understanding of what gives coral species their best chance of survival is crucial in a warming world. “Coral reefs are the most biodiverse place in the ocean, and the basis of its food chain,” Reckenbeil says. “They are the rainforests of the ocean.”