Daniel Proud, assistant professor of biology, and student-researcher Cielo Disla ’25 examine some dissecting tools and discuss how to dissect harvestmen. (photo: John Kish IV)

On a dark night in the Costa Rican rainforest, Assistant Professor of Biology Daniel Proud and students from his research lab don headlamps and search for and collect Opiliones, aka harvestmen. You may know them as daddy longlegs, so named for their needle-slender appendages that are exceedingly long relative to their bodies. Harvestmen are nocturnal. The larger ones can be spotted crawling on the ground, rocks, and trees. To collect the smaller harvestmen, Proud and his student-researchers scoop up, sift, and search through leaf litter from the forest floor.

Advancing Scientific Understanding

The collection of specimens is part of a five-year research project made possible by an $888,044 CAREER grant awarded to Proud by the National Science Foundation Division of Environmental Biology (NSF-DEB award # 2337605). The project is titled “CAREER: Investigating Biogeographic Hypotheses and Drivers of Diversification in Neotropical Harvestmen (Opiliones: Laniatores) Using Ultraconserved Elements.” The aim of the research is to advance understanding of how species diversity has been shaped by evolutionary processes linked to geological and climatic histories. Researchers expect to discover and describe dozens of new species.

in Costa Rica

Okay, but why study daddy longlegs? Proud explains: They are diverse—there are more than 6,500 species known to science, and many more waiting to be discovered. They have ancient origins and are found around the world. Despite their global distribution, they don’t travel very far, and so they tend to be unique to a region.

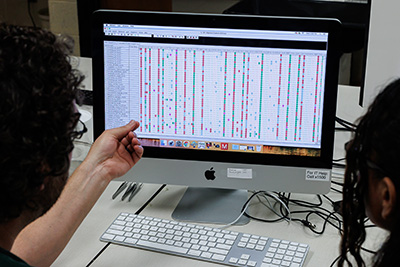

Proud’s student-researchers will work with advanced technology to generate and analyze genetic data for the harvestmen they’ve collected and create a phylogenetic tree that illustrates the evolutionary relationships of Opiliones.

The phylogenetic tree can then be time-calibrated to dig deeper into their evolutionary history. “We know that genes change at certain rates, and we can use that information to estimate how long ago two species diverged,” says Proud. Fossils also help to calibrate the tree. Then by looking at the geological and geographical history at the time two species diverged, researchers can identify the likely cause—a geological shift, a climatic change, a long-distance dispersal, or another major event.

“For example,” says Proud, “There’s a mountain range that cuts through Costa Rica into Panama, and I’ve never seen a species of harvestman that occurs on both the east and west sides of the range. Still, the species on the east and west might be closely related. Perhaps the formation of the mountains separated a single species on both sides, and after living apart for so long—maybe a million years—two new species formed in their different environments.”

The geology of Central America and the Caribbean islands offers a rich location for this research. For example, the formation of the Panamanian isthmus, the land bridge that connects North and South America, was a geological event that had a huge impact on Earth’s climate and environment, which in turn likely affected species diversification. And, approximately 34 million years ago, some Caribbean islands may have been connected to South America by the Greater Antilles-Aves Ridge land bridge (GAARlandia).

Enriching Student Experience

Proud’s research will advance, globally, our understanding of the processes that generate and maintain biodiversity, but it will also have important impacts here at home. Undergraduate students will be trained to use powerful bioinformatic tools, cutting-edge molecular methods, and advanced microscopy techniques—skills that they can take with them to graduate school. The funding will also enable Proud to train and mentor a postdoctoral fellow for up to three years.

Back in Proud’s lab at Moravian, students will sort, organize, and identify the thousands of specimens they’ve collected, representing hundreds of different harvestmen species. The focal taxa will primarily consist of two lineages, or groups: Cosmetidae, “a family of large, colorful, charismatic Opiliones,” Proud describes, and Zalmoxoidea + Samooidea, a group of small litter-dwelling harvestmen.

The team will use ultraconserved elements (UCEs) to build phylogenetic trees and test their hypotheses. UCEs are regions of the genome that are shared across distantly related groups (e.g., reptiles and mammals), and they can be captured with a specially designed probe set. Adjacent to the UCEs, there are variable regions of DNA that contain information that can be used to reconstruct evolutionary relationships between species. Students will use a probe set designed specifically for Opiliones to target 1,915 UCEs.

Each summer, students will spend several weeks extracting DNA from tissues in the legs of harvestmen and hybridizing the DNA with the UCE probe set. After obtaining the sequence data, student-researchers will learn to use advanced bioinformatic tools to build the harvestmen “family tree.”

In addition to hands-on field- and laboratory-based research, the grant will fund travel for student-researchers to attend international and national conferences. And both science and nonscience majors will have the opportunity to engage in international travel and field research through the travel course Tropical Biodiversity and Conservation of Costa Rica. The research team will develop educational resources, in English and Spanish, to share with K–12 students and public audiences, both locally and abroad.

The overlooked, unassuming daddy longlegs have a very long and valuable reach in science and student experience.—Claire Kowalchik