Maker:L,Date:2017-9-21,Ver:5,Lens:Kan03,Act:Kan02,E-Y

I have always been meaning to go to Japan and I knew that it was only a matter of time before I found myself there for one reason or another. However, I didn’t imagine that I would be there studying for college.

I imagined that I would be going years later to study endemic fauna, but instead, I found myself here through some rather convincing words. Since this was my first time in Japan, I set a few goals for myself that I made my top priority to fulfill, alongside the objectives of the May Term program. Among these goals: to visit a Pokémon Center; go to the Yamato Museum; go hiking somewhere; and to find the Japanese Giant Salamander (known locally as the ōsanshōuo, which roughly translates to giant pepper fish).

Most of the students accompanying me can attest to this and remember when I told them that if I were to see a Japanese Giant Salamander, I would jump in to wrangle it and have one of them film it. In hindsight, that likely would have been illegal considering the creature’s protected status and its reputation as a national landmark of Japan. Now, one of these was much less likely to be completed than the others, but I was still set on looking everywhere I could for this elusive amphibian no matter how few and far between those opportunities were, or how improbable it would be to find it in the areas we were visiting as they were mostly urban areas with less than stellar water quality.

None of these goals were part of the ultimate mission, however, so they would have to wait until those were complete. That ultimate goal was for us to immerse ourselves in the culture of Japan and to better understand the context of the deployment of the atomic bombs as a crux from which to further establish peace.

So, I may not have actually seen the Giant Salamander, but I am confident that I at least heard one splashing around in Kyoto. The other goals, however, were all met. The hike up and down Mt. Misen at Miyajima was an absolute delight and easily one of, if not the, best part of the experience for me. Whenever I travel to a new place, I always look for a good place to hike so I can get closer to nature and see the unique experiences it has to offer. This photo is just one view on the path to the top and this was just one of three paths to take. I just wish I had enough time to do all of them.

My original plan for the Yamato Museum was to go during free time on Tuesday, but of course the museum was closed on Tuesday for whatever reason. Instead, I was able to negotiate a trip to the museum during another activity in Hiroshima and got many of my friends to accompany me.

The centerpiece and namesake of the museum—the Japanese battleship Yamato—was the largest battleship ever built with the largest guns ever mounted on a warship and the primary inspiration for my interest in naval warfare and history. As a result, I knew about this museum for a long time and had it among the top places on my list to visit had I ever found myself in Japan. Yet nobody else knew about this location until I told them about it.

The museum was built on the drydock where the ship was constructed and was one of the proudest works of the city, which is famous for its construction of warships. It was actually similar to Bethlehem in that it became successful due to a major product that was no longer viable after the war and fell into disrepair and poverty before bouncing back later. The city’s close location to the Hiroshima prefecture likely contributed to its selection as a target for the atomic bomb as Mitsubishi’s factories that mainly built torpedoes were nearby in the main city.

The most pivotal battles of the Pacific War were fought on the seas with warships that came from Kure and Hiroshima, such as the Yamato. But Japan realized too little too late that power over the waves was not based on battleships like Yamato, but instead on carriers, most of which were destroyed at Midway, neutering the Japanese Navy for the rest of its brief and bloody history. Even Yamato’s might could not carry the fleet as she was too expensive to maintain and too valuable to send into battle without massive escort.

Yamato went on her suicide mission to Okinawa as a last desperate move to slow the American advance. Learning more about the story of Yamato in her place of origin helped me to better understand the reasoning behind the atomic bombs, as they showed how far Japan was being pushed back and what they had to resort to in order to stave off their adversaries.

At the same time, Japan’s government refused to allow for a peaceful surrender even after losing Yamato and Okinawa, giving the American government the opportunity that it was looking for to deploy the bombs. The attitude of Yamato’s crew reflected that of most, if not all, of Japan by August 6th. Just as Yamato was a symbol of power for the old Japan, one could interpret its demise as both a stepping-stone towards the bombs and the first step towards the peaceful Japan that exists today.

Though I did not realize it at first, I believe that Yamato’s story and the museum dedicated to her puts our objective of peace into greater context as it provides a glimpse into what Japan was like before the bombs, showing a stark contrast between the warlike society of the past and the Japan of today that would give seemingly anything to maintain peace.

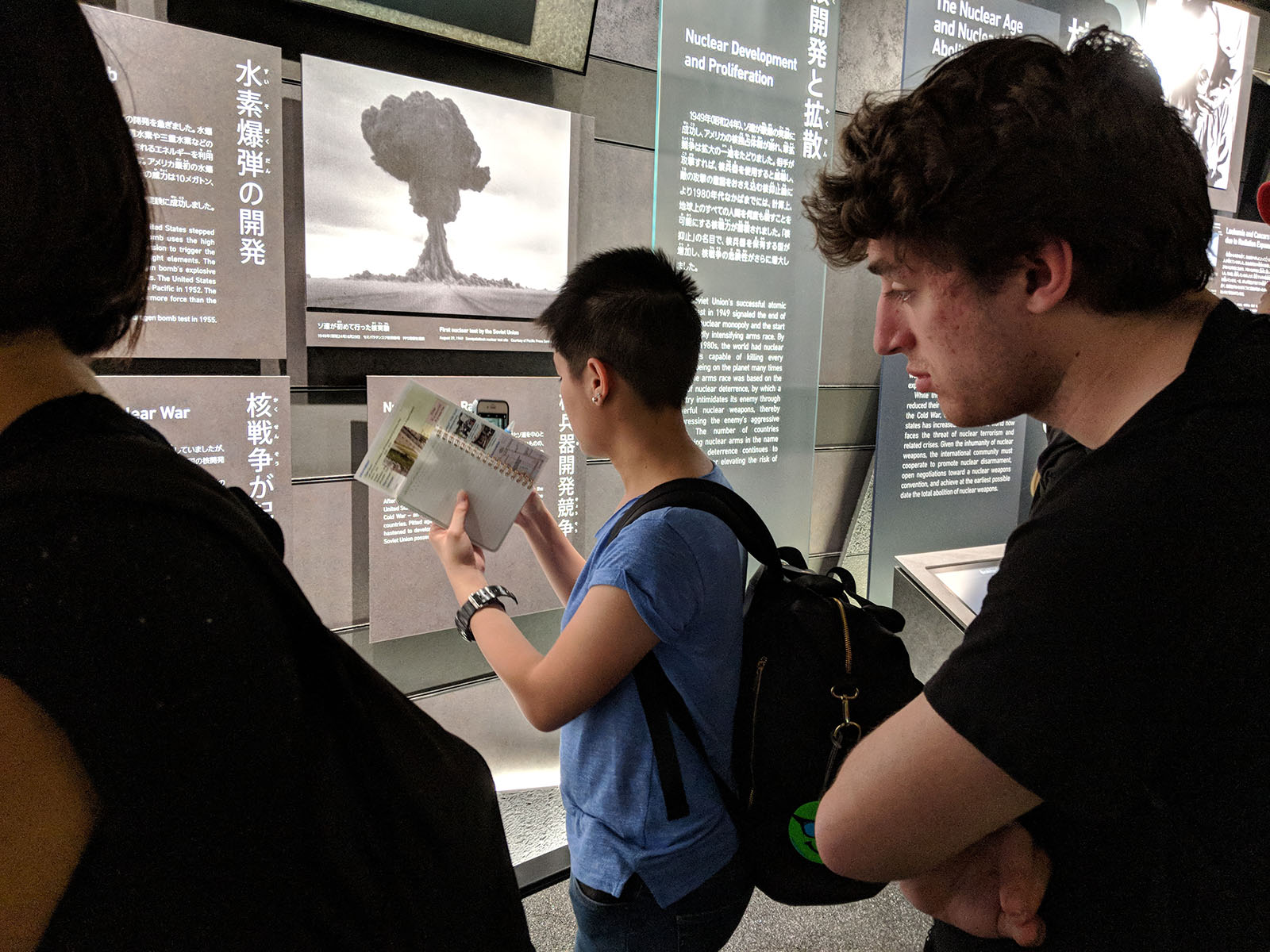

Something that stuck out to me about the peace museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was just how different they were. I expected them to both be roughly the same, but they took opposite approaches to addressing the bombings. In Nagasaki, it is mostly focused on the facts and presenting what happened as it was, rather than trying to use pathos or influencing emotions, whereas Hiroshima goes full force in this department. Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park mainly focuses on making the attendees feel the gravity of what happened and put them in the shoes of the victims. I understand the reasons for both methods and learned more about their approaches through how they were presented in the museums I visited.

The contents of both museums, such as the prominence of water and the art depicting what the victims saw, was what lingered with my group the most, though that may have been because we were asked to analyze it and pick out the one that most deeply resonates with us. Much of the work assigned during the day was like this, and it was effective because it forced us to be observant and analyze what we were looking at to find out just what about the art or the monuments made us think or feel the way we did.

The peace museums made me think of the Yamato Museum because to me, they are all windows into what has been lost and how no matter how hard we may try some things can never be truly rebuilt. Just as what Yamato and what she represented are lost below the waves, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki that stood on their own without living in the shadow of the atomic bomb are gone forever. The cities will never be free of that baggage, but it is one that must be carried in the name of teaching it to our children.

When I was in Japan, I took in what I saw day by day and thought about each day and what I witnessed by itself. Only when it was all said and done did I really have the opportunity to think about what I learned in context. I always understood that history and cultures are dynamic and rarely, if ever, progress in a style that could be considered as linear. I do not even think it is entirely accurate to say that there is strict progression.

The most significant thing I took away from my stay in Japan was the transformation of an aggressive imperialist nation, with one of the most famous and powerful armed forces in the world at that time, into one of the world’s leading advocates for peace through experiencing the brutality of war and the new means through which it was waged. Radical paradigm shifts such as these typically only occur under unfathomable circumstances, as even those involved in the Manhattan Project likely had little idea of what the atomic bombs were truly capable of, or what they would turn into. Only when that power was unleashed did the modern world realize how crucial it was to maintain peace, as the consequences of failure in that area were now on full display.

Being in Japan and witnessing all of these places and events has turned out to be one of the defining experiences of my life. I had the opportunity to see a country that was always so close yet so far. I had so many burning questions and I still do now, but many of these new questions have come up because of the answers to ones that I was wondering about and from my observations when I arrived. I would say that actually provides incentive for me to return, which I most certainly will once I get the chance. That’s how you know you’ve been on a highly fruitful trip—when you can’t wait to return.