“Close your eyes. Sit in silence and stillness, and pray for Universal Peace in your mind, all together as an audience. When the lights come back up, please open your eyes. Then return to your homes, taking with you the petal of SAKURA deep in your heart.”

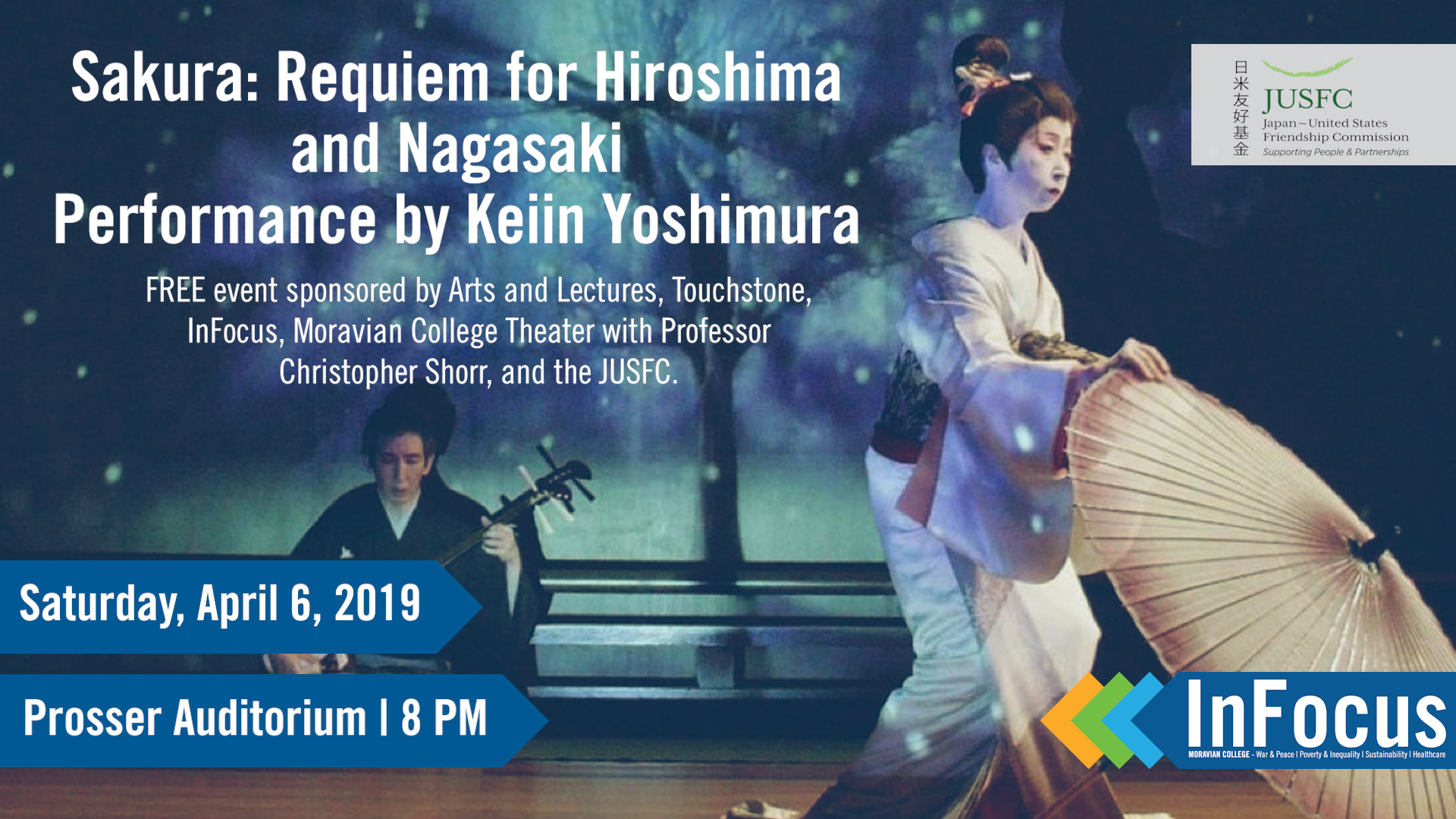

Those were the words printed on the program for the April 6 performance of Sakura: A Requiem for Hiroshima and Nagasaki by Keiin Yoshimura held in Moravian’s Prosser Auditorium.

After viewing Sakura, I was left in a state of questioning. The audience was asked not to clap after the performance but simply sit and reflect. It was an interesting choice for Yoshimura to request this, but by the end of the dance, you almost forgot about applauding. You were filled with a sense of confusion, urgency, and sadness and didn’t think about thanking her for the performance. It was clear that this is what Yoshimura wanted; she wanted the focus to be on the message of the piece.

This is typical of traditional Kamigata-mai dance. In this style, the story and the character are more important than the movement quality. Generally speaking, dance requires a challenging balance between telling the story and evoking thoughtful movement. Depending on the story or emotion, this balance can look or feel very different. For Yoshimura, the balance shifted to the story she told.

The piece was aided by Japanese poetry. Every member of the audience was given the chance to read and digest the poetry before heading into the performance. Reading these eight poems set the tone for the dance.

Immediately at the beginning of the dance, Yoshimura portrayed a powerful combination of heartache and anger. A silver foil-like material covered the floor, and a backdrop displayed visuals that aided the recorded poetry. Movement started from underneath the foil, and Yoshimura appeared as if coming out of the soil on the ground. Her movement and emotions were urgent yet confused and unsettled, and though she wore a mask, those emotions were distinct. Yoshimura clutched the foil as if it was everything she had lost. The audience felt her pain.

Then came the sound of water trickling as Yoshimura explored feelings of calm and serenity. She breathed visibly with movement that was shaky, as if she was trying to walk again. She conveyed a rebirth, though one marred by loss. Yoshimura performed some of her movements with a bo, a staff-like instrument from traditional Japanese culture. She used clear, sharp moves that worked to release the anger she was feeling, and she repeated her movements in this section three or four times and used her voice to make sure we saw her and felt her pain and heartache.

The final portion of the piece was very stoic, almost cold. There were moments where Yoshimura portrayed grief and hurt but then worked to pull herself back to stoicism. She changed her appearance on stage, adding layers of clothing as a symbol of her attempt to rebuild her identity and push through her emotions. To me, however, these many layers of clothing seemed to keep everything in, to contain the ever-present sadness. Yoshimura moved quietly around the stage. It was clear she was still working through her sadness but had regained her purpose in life. The sakura—cherry blossom—had regrown.

Yoshimura’s composition and performance was breathtaking and unexpected. She filled the stage and room with continuous emotion that affected each and every member of the audience. Her performance was light in movement but clear and brilliant in its story-telling. As a dancer, I understand the constant balance between movement and story-telling, and Yoshimura’s choice to focus on emotion was beautiful. She took the horrifying event of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and transformed it into a powerful piece about sadness, rebirth, and peace. She instilled in us wonder, discovery, and a “petal of SAKURA deep in [our] heart[s].”